Want to save Indian waterbirds? Protect these two wetlands!

by Shalini Jain

Figure 1 Flock of demoiselle cranes (Grus virgo) at the study sites.

Waterbirds, a globally distributed and species-rich avian group, play a crucial role as ecosystem sentinels for wetlands—essential habitats supporting diverse plant and animal life. Unfortunately, India, home to the highest number of threatened inland-breeding waterbirds, faces inadequate protection for its wetlands. One contributing factor to this deficiency is the limited knowledge about potential waterbird breeding sites within India.

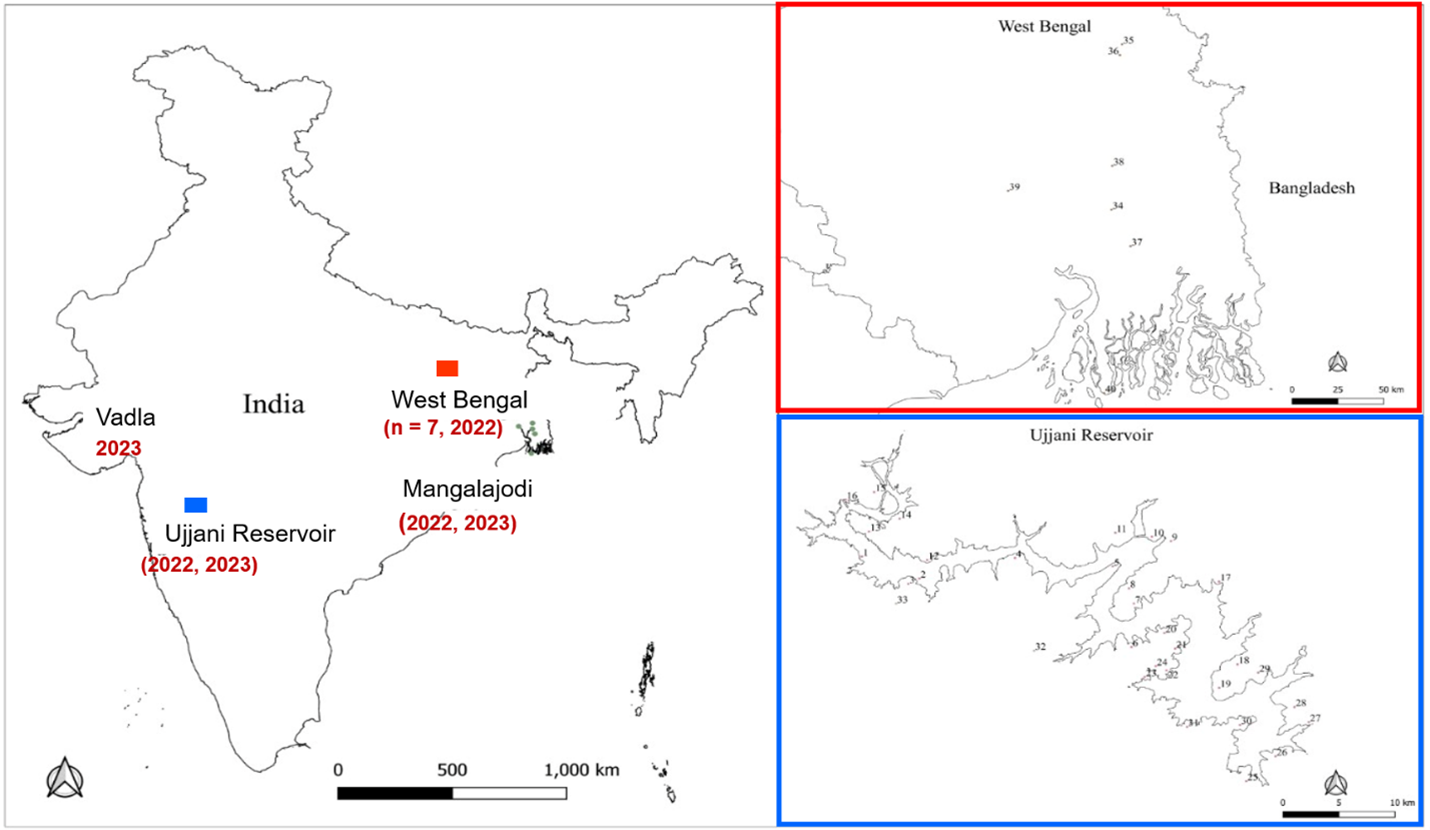

Figure 2 Panels in map show the survey sites studied in India.

To address this issue, during the summers of 2022 and 2023, Mayank Shukla and I conducted surveys in selected wetlands across four major states: Odisha, West Bengal, Gujarat, and Maharashtra (Figure 2). Our primary objectives were twofold: first, to document the diversity and number of waterbirds during the breeding season, and second, to observe and record evidence of nesting behavior for all waterbirds.

Figure 3 Flock of glossy ibis (Plegadis falcinellus) and garganey (Anas querquedula) in flight.

We actively searched for nests, chicks, fledglings, and broods, conducting scan-sampling to assess the total number of waterbirds across nine sites in 2022, including Mangalajodi, AJCB Indian Botanical Garden, Purbasthali Bird Sanctuary, Koblar Bill, Baruipur Wetland and Marsh, Diara, Ghatal, Laxmipur Abad, and Ujjani Reservoir. In 2023, we focused our survey efforts on three sites: Mangalajodi, Vadla, and Ujjani Reservoir.

Figure 4 Black-winged stilt (Himantopus himantopus) chicks meters away from a grazing livestock.

Our findings were both surprising and concerning. Overall, we documented 78 different waterbird species across all sites, with eight of them being globally threatened species. Alarmingly, we noted a significant level of human disturbances in the areas, including extensive fishing, agriculture, tourism, and livestock grazing (Figure 4). Furthermore, we made a rare observation of an Oriental pratincole egg laid in the nest of an entirely different species, the Black-winged stilt.

Figure 5 An adult male great painted-snipe (Rostratula benghalensis) with two of his chicks.

Most importantly, we discovered that to preserve Indian breeding waterbirds, prioritizing the protection of Mangalajodi Wetland and Ujjani Reservoir is crucial. This is due to their exceptional diversity, each hosting around three dozen different waterbird species. Furthermore, the presence of globally threatened waterbirds in both sites underscores their significance for current and future endangered species. Notably, Ujjani Reservoir alone supported over 100 nests and chicks.

‘We discovered that to preserve Indian breeding waterbirds, prioritizing the protection of Mangalajodi Wetland and Ujjani Reservoir is crucial.’

In summary, Mangalajodi and Ujjani Reservoir hosted the largest congregations of waterbirds, yet they currently lack legal protection. We hope that these preliminary results propel us towards establishing an effective wetland protection system in India. Finally, I express gratitude for the unwavering support of Prof Yu-Hsun Hsu and Prof Tamás Székely, as without it, this work would not have been possible.

Figure 6 Bronze-winged jacana (Metopidius indicus) walking with its chicks.

Shalini Jain, a PhD student at the National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan, is interested in behavioural ecology and evolutionary biology. She is currently researching the demographic and ecological drivers of the demographic dynamics of the Greater Painted-Snipe. She has previously published natural history observations of Indian birds, like of the Terek Sandpipers, and Lesser Flamingos.